Health System Resilience

Establishing cancer care central to an emergency response plan in all conflict settings requires rebuilding cancer care infrastructure and strengthening the workforce through international cooperation.

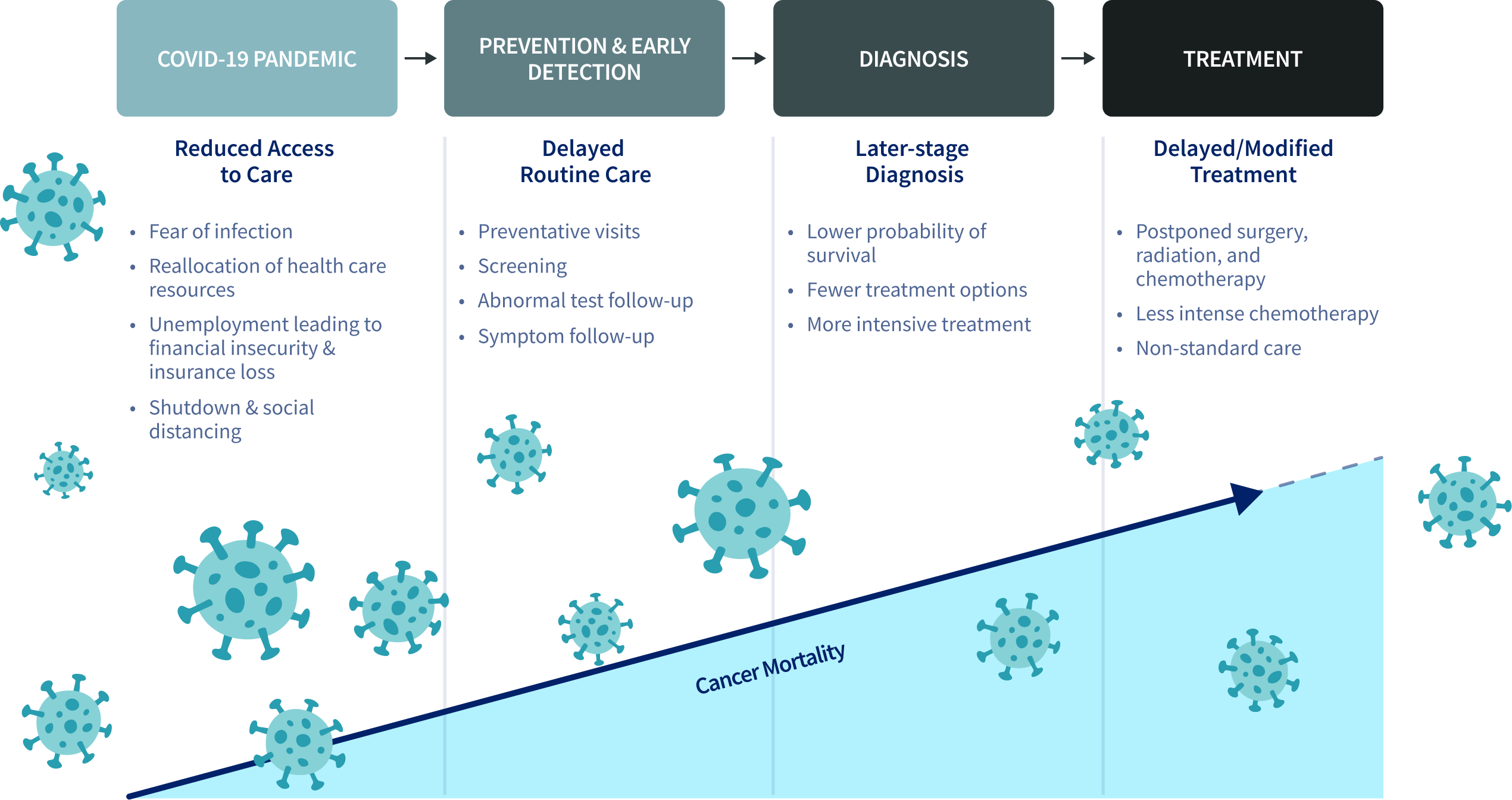

Nearly 7 million lives were lost due to COVID-19 during the 2020-2023 pandemic. Patients with cancer were affected both directly and indirectly by the disease (Figure 47.1).

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the cancer continuum

Patients recently diagnosed with cancer or undergoing active treatment, often being immunocompromised, faced a higher risk of COVID-19 mortality than the general population, with those with lung and hematological cancers carrying the greatest risk. One study estimated there were 39% fewer screenings for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers in 16 countries where diagnostics and screening activities were suspended. Routine cancer treatments were disrupted with a reported 28% decrease in services (Figure 47.2). Countries made health system adjustments, such as rapid vaccination, specialized diagnostic pathways, and modified treatment locations and protocols to reduce hospital visits, yet it remains inconclusive if these efforts have reduced COVID-19 deaths among cancer patients.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer diagnostics and services by four-tier Human Development Index (HDI)

Global cancer care communities also face numerous humanitarian crises amid rising international and regional conflicts, posing complex challenges. In affected areas, these situations often lead to (acute) collapse of health care systems and long-term impact, including cancer care. Sudden large-scale migrations strain local and national health care systems, which are often unprepared for the influx, leading to inadequate cancer diagnosis and care for migrants. Studies have shown that refugees experience later disease presentation, delayed diagnosis, and higher rates of treatment abandonment, leading to lower survival proportions (Figure 47.3). The need for reactive and adaptable health systems is evident to reduce the impact of crises on cancer risk and outcomes.

5-Year observed survival among Syrian refugee adults and children with cancer compared with local residents in Türkiye

ADULTS

CHILDREN

Footnote

Adult observed survival data acquired through GCO SURVCAN. Children net survival acquired through CONCORD-3. CNS: Central nervous system.

“The greater the force of your compassion, the greater your resilience in confronting hardships.”

New international voices have emerged to empower the delivery of better cancer care for conflict-impacted populations (Figure 47.4) and to build a resilient health system capable of mitigating the effects of future crises (Figure 47.5). Pandemics and conflicts have worsened inequalities both across and within countries, disproportionally affecting underserved subpopulations in countries with already fragile health systems. Although data on cancer in crisis and conflict areas remains limited, monitoring these impacts, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, is vital to understanding long-term effects.

Seven key recommendations from the manifesto on improving cancer care in conflict-impacted populations

Footnote

Adapted from Ghebreyesus TA, Mired D, Sullivan R, et al. A manifesto on improving cancer care in conflict-impacted populations. The Lancet. 2024;404(10451):427.

Pillars to strengthen health system resilience to mitigate impact of crises