Social Inequalities

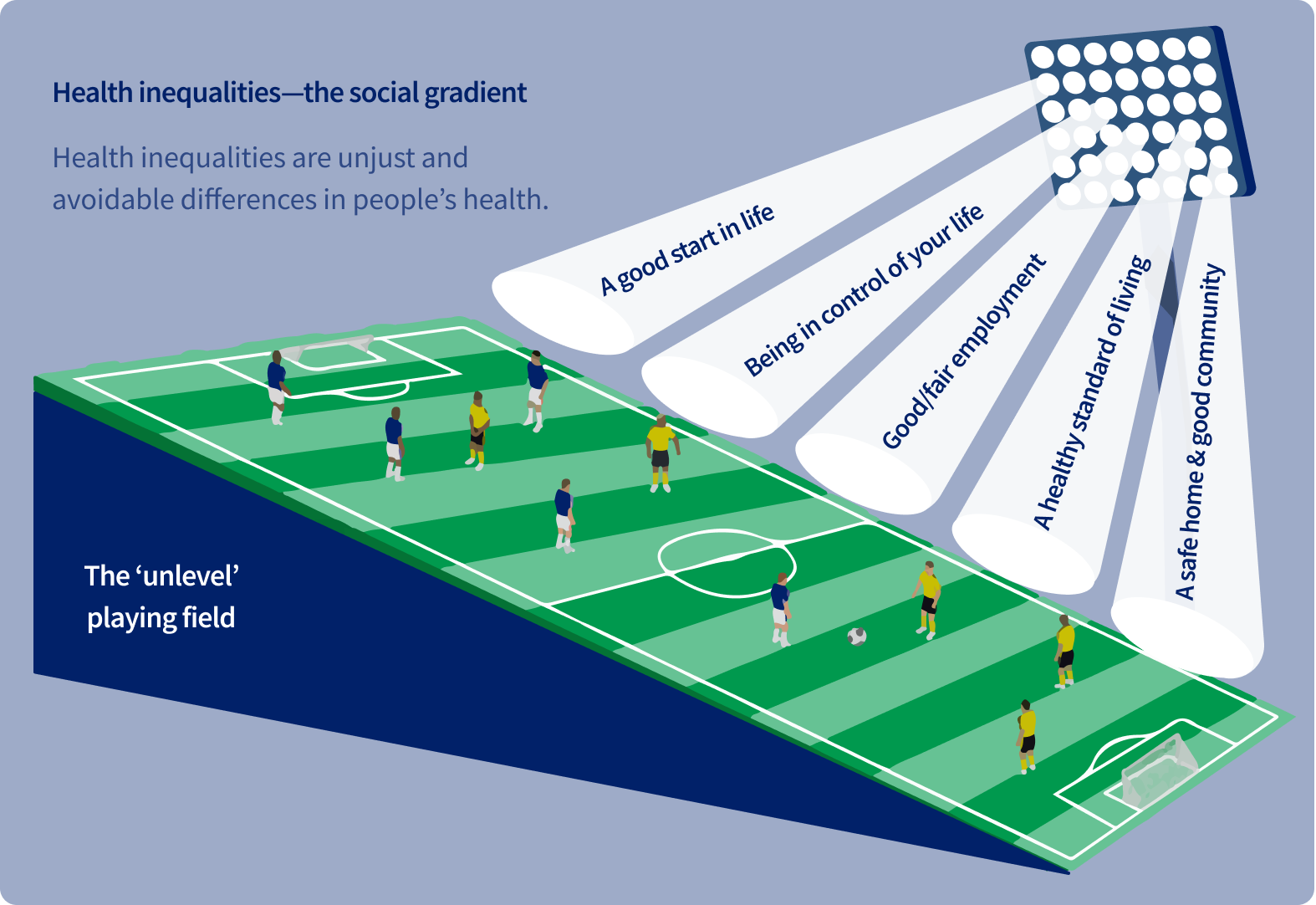

With sufficient investment, cancer prevention can mitigate the marked cancer inequalities that exist between and within countries worldwide. Health inequalities refer to differences in people’s health that are unjust and avoidable (Figure 13.1) and may relate to differences between groups based on, among others, socioeconomic position, race or ethnicity, sex, disability, gender, migration status, or place of residence. For cancer, inequalities in the cancer burden may exist throughout the entire continuum: from prevention, early diagnosis and detection, to the likelihood of receiving and accessing timely and effective cancer treatment, to accessing palliative care.

Representation of the structural determinants of health

Cancer inequalities across countries are evidenced by differences in the magnitude of national cancer-specific incidence, mortality rates, and survival. For example, the hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine became available much earlier in high-income countries, which lowered the prevalence of HBV infections and liver cancer incidence and mortality today. In contrast, low-income countries, where vaccination would have the greatest impact, still face higher rates of HBV-associated liver cancer (Map 18.1).

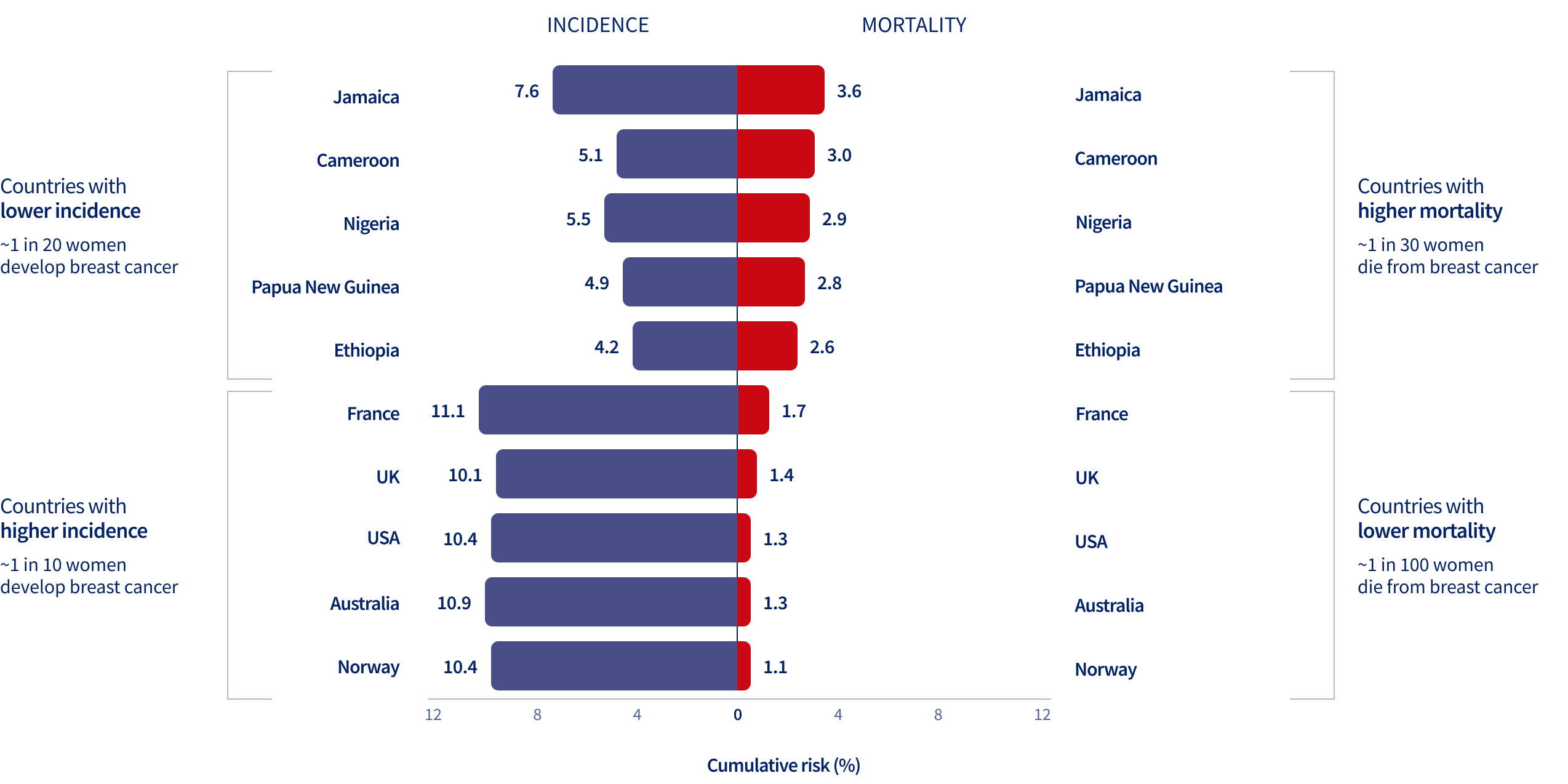

Breast cancer incidence rates in very high-income countries are among the highest globally, with 1 in 10 women diagnosed with the disease in their lifetime, yet one in 100 women dying from the disease (Figure 13.2). This contrasts with low-income countries, where breast cancer mortality rates are among the highest globally, and where one in 20 women are diagnosed with the disease in their lifetime, yet closer to one in 30 women die from it. The high risk of breast cancer death in the low-income countries despite their low risk of developing the disease reflects a lack of or limited early detection and treatment services.

Breast cancer mortality is considerably higher in low-income compared with high-income countries despite their lower incidence due to inequalities in early detection and treatment.

Estimated cumulative risk (%) of female breast cancer incidence and mortality before age 75 in ten countries, 2022

“Health inequalities and the social determinants of health are not a footnote to the determinants of health. They are the main issue.”

Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer rates between countries are paralleled by those within countries, as Figure 13.3 illustrates for cervical cancer mortality in selected European countries. Countries in Central/Eastern Europe (with relatively lower average education) have higher cervical cancer mortality – despite having lower incidence rates – than those in Northern/Western Europe (with relatively higher average education). The variability in cervical cancer mortality among higher-education groups is relatively small, with much of the disparities between countries found within lower-education groups.

Educational inequalities between and within countries in cervical cancer mortality in Europe, by sex, 1998-2015

Footnote

The period of observation varies between 1998 and 2015, depending on the country.

Preventative strategies offer an effective mechanism to mitigate social inequalities in cancer. At present, the disproportionately lower investment in policies of cancer prevention relative to treatment, for example, in precision oncology, may have the opposite effect, whereby existing inequalities are exacerbated.