Body Fatness, Physical Activity, and Diet

Over 80% of adolescents are not meeting physical activity guidelines for cancer prevention.

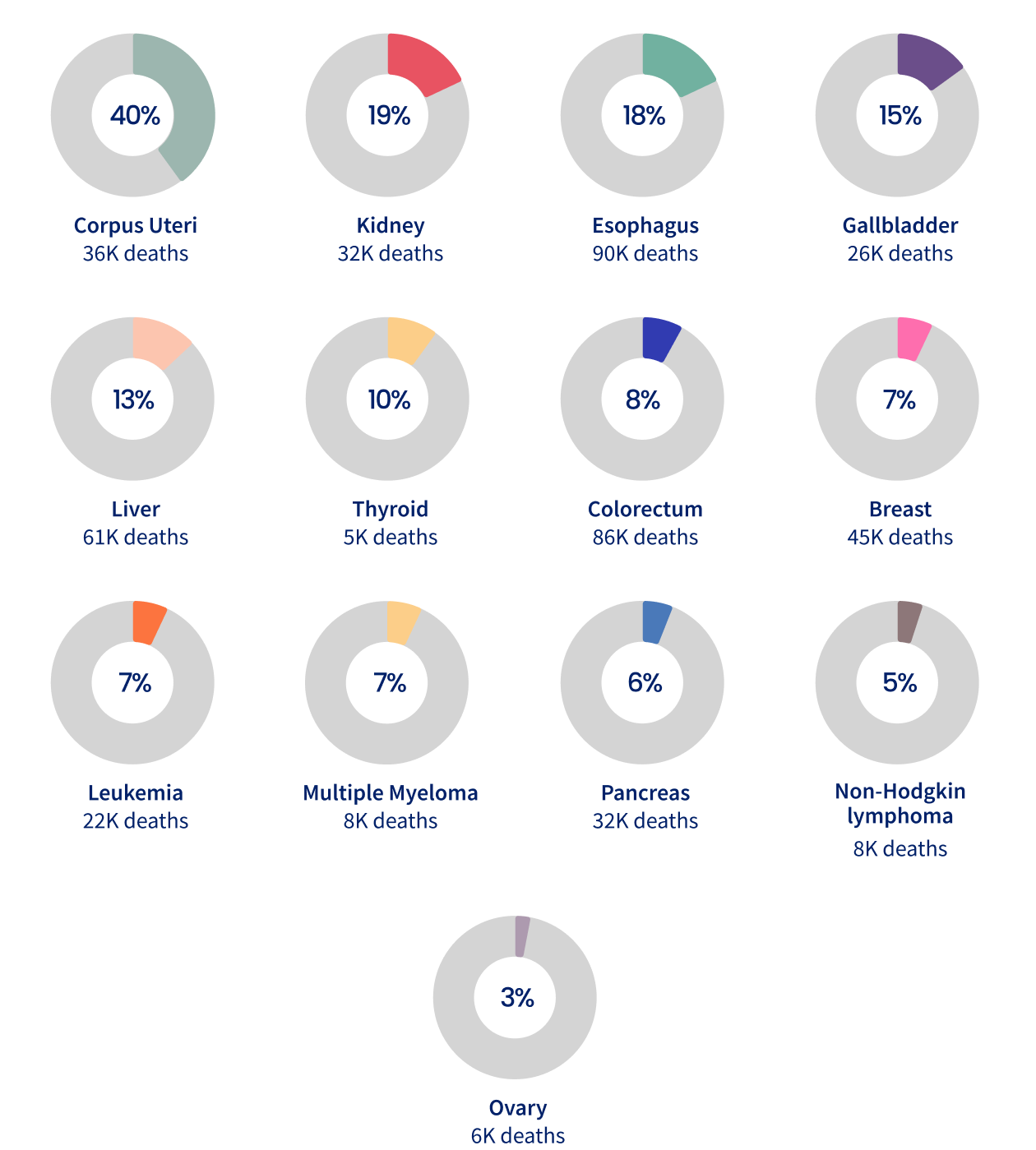

Excess body fatness – overweight and obesity – has been linked to at least 13 types of cancer. Overall, approximately 4.5% of all cancer deaths globally are attributable to excess body fatness, varying from <1% in low-income countries to 7-8% in some high-income countries. The proportion of deaths linked to excess body fatness differ by cancer type, with an estimated 40% of uterine cancer deaths, followed by 19% of kidney cancer deaths, and 18% from esophageal adenocarcinoma deaths (Figure 6.1).

Excess body fatness causes 440,000 cancer deaths globally.

Proportion (%) of cancer deaths attributable to excess body fatness by cancer type, 2021

“Lack of activity destroys the good condition of human beings, while movement and methodical physical exercise save it and preserve it.”

The prevalence of excess body weight substantially varies across the world, with the highest prevalence found in parts of North America and the Middle East and lowest prevalence in parts of Africa (Map 6.1).

While unhealthy diet and physical inactivity contribute to excess body fatness, they also influence cancer risk independently of body weight. Emerging evidence highlights the link between greater consumption of ultra-processed foods and increased risk of a wide range of noncommunicable diseases, including cancer. Consumption of ultra-processed foods has risen globally (Figure 6.2), fueled by factors such as convenience, affordability, aggressive marketing, urbanization, and their addictive palatability.

Ultra-processed food sales (kg) per capita by WHO region, 2024

A healthy dietary pattern, rich in a variety of plant foods, and low in red and processed meat, reduces the risk of certain cancers (Figure 6.3).

Summary of evidence on body fatness, physical activity, diet, and cancer risk

Footnote

Conclusions on body fatness are based on Lauby-Secretan B et al. Body Fatness and Cancer--Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. The New England Journal of Medicine. Aug 25 2016;375(8):794-8 and are and are supplemented from the Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018, World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research: Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancer: a global perspective. Continuous update project expert report 2018 (WCRF 2018). Conclusions on physical activity are drawn from 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2018. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and are supplemented with ECRF 2018. Conclusions on dietary factors are based on WCRF 2018.

Being physically active reduces the risk of cancers of the bladder, breast, colon, endometrium, kidney, stomach, and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Nevertheless, over a quarter of adults do not meet the World Health Organization physical activity guidelines worldwide, and over 80% of adolescents are insufficiently active (Figure 6.4).

Age-standardized prevalence (%) of insufficient physical activity among adults (18+ years) in 2022 and adolescents (11-17 years) in 2016

Adults

Adolescents

Footnote

Insufficient physical activity is defined as less than 60 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity daily.

Promoting healthy eating and active living to reverse the obesity epidemic holds considerable potential for reducing cancer incidence and mortality. Ensuring advances in these areas will require a comprehensive approach to improve equitable access to healthy food, address commercial influences on food supply, and improve the built environment through partnerships among public, private, and community organizations.

While strong, locally tailored health promotion and policies have shown promise, reversing the unfavorable trends in body fatness, diet quality, and physical inactivity will require additional resources, sustained political commitment, and global coordination (see Health Promotion).